Submitted by Lilian C. J. Wong, B.Sc., M.A., Ph.D., Vice President, Meaning-Centered Counselling Institute

Introduction

As a brand new mathematics and science high school teacher in Ontario, I was assigned as the guidance teacher for a class. I enjoyed working and guiding students so much that I became a Guidance Specialist. Then I realized that I was not equipped to help students who had problems focusing, difficulties relating to peers, and symptoms of distress. An announcement of a Play Therapy workshop caught my attention. I eagerly attended the workshop without knowing what play therapy was.

After many years of training in play therapy, and having used it all through my professional career as Psycho-Educational Consultant, School Psychologist, Professor of Counselling Psychology and psychotherapist, I have learned to appreciate Play Therapy (PT) as one of the most powerful therapeutic tools for healing and positive change. Unfortunately, I have met so many people who have the misconception that Play Therapy is only good for children. I hope that this article will help readers gain a better understanding of PT as a therapeutic modality for all people.

What is play therapy?

Play Therapy has a long history in the field of psychotherapy. Sigmund Freud first recognized the importance of children’s play, and Anna Freud incorporated play activities into therapy. Carl Jung also recognized the therapeutic importance of play because of its rich symbolic meaning. Melanie Klein (1932/1955) often interpreted the meaning of play in therapy, and Dora Kalff (1980) integrated her Jungian training with sandplay.

For little children, playing is all they do. The world is their playground. As pointed out by Gary Landreth, play is the singular central activity of childhood, occurring at all times and in all places. Play is spontaneous, enjoyable, voluntary, and non-goal directed (Landreth, 2002). Others also value play in the healing process, for examples, Axline (1947) stated that “Play is the child’s natural medium of self- expression” (p. 9), and Ginott (1994) recognized that, “A child’s play is his talk and toys are his words” (p. 33).

Gary Landreth, an internationally known leader in PT, considers play as children’s symbolic language that provides a way for them to express their experiences and emotions in a natural, self-healing process. Play is therapeutic when it is an integral part of counselling

Landreth defines Play Therapy as a dynamic interpersonal relationship between a child and a therapist trained in play therapy procedures who provides selected play materials and facilitates the development of a safe relationship for the child to fully express and explore self (feelings, thoughts and behaviors) through the child’s natural medium of communication – play.

For adolescents and young adults, play is still a major part of their lives, perhaps, second only to schoolwork. Their form of play is more likely to involve peers, such as socializing, playing sports, and joining clubs.

What happens to adults? With increasing responsibilities and demands, adults have less time for play. However, they still need leisure activities to provide some relief from everyday stress. It seems that adults prefer passive play in the form of participating in spectator sports, watching TV, etc.

For retired seniors, they again have more free time on their hand, and can enjoy their second childhood. In nursing homes, there are recreational activities organized by the staff for their residents.

In one form or another, play is always a part of our lives and a major contributor to our happiness and well-being. People play simply for the enjoyment of it. Play is a powerful intrinsic motivation.

Why is play so important?

Play is a spontaneous process that allows an individual to engage in an activity either physical or mental. There are many forms of play: active, passive, group or solo. It may involve thinking, feeling, moving, creating, focusing or team work. Play is relaxing, pleasurable, happening in the here-and-now, and involving the self in various degrees. It may even entail the “flow” experience, in which one loses oneself in an engaging and challenging game. As a leisure activity, play offers individuals the freedom to explore, to enjoy, and to be oneself.

Like all other mammals, children learn through playing. They learn how to balance their bodies and coordinate their hands and feet. They learn about their likes and dislikes, strengths and weaknesses. They learn how to cooperate with other children, relate to adults, and exercise self-control. They discover boundaries and something about the world in which they live.

According to Piaget, play is children’s means of making sense of their experience in order to make it part of themselves. Bruner (1983), an educational psychologist, stated, “The play under the control of the player gives to the child his first and the most crucial opportunity to have the courage to think, to talk and perhaps even to be himself” (p. 69).

Similarly, Eric Erickson said, “Making sense of the world is an enormous task for young children … Then ‘solitary play remains an indispensable harbour for the overhauling of shattered emotions after periods of rough going in the social seas’ … (Erikson 1965:214-215)” (McMahon, 2005, p. 2).

For adults, play is an important source of positive emotions, that we all need to stay mentally healthy and productive. With games that include the whole family or group of friends, playing together improves relationships and bonding.

Dr. Stuart Brown (2012), psychiatrist and founder of the National Institute for Play discovered that playing together helped couples rekindle their relationship, and explore other forms of emotional intimacy. This finding also confirms in my own practice that leads me to conclude: “The family that plays together, stays together.” Research by Chris Peterson (2013) has also shown that play is an important domain for living a meaningful life.

Play Therapy is not only effective modality of psychotherapy with children and family, it is also inherently cross-cultural. Down through history in all continents, play is an important part of cultures. They might have different tools, games, and rules, but for all participants, play is a “state of being,” as Stuart Brown called it, “purposeless, fun and pleasurable” (2012).

The role of play therapy in mental health

In my practice, play therapy is effective in working with children, adolescents, adults, and families. In this paper, I want to make a case that play therapy is a powerful and effective tool in any psychotherapist’s toolbox, and play is essential for a healthy life through all stages of human development.

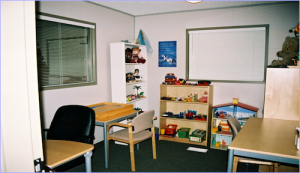

Play Therapy employs a wide range of modalities, such as sand tray activities, drawing and art therapy, puppets, doll house, role play and drama, and well selected games. In general, Play Therapy can be directive or non-directive, or the combination of both, depending on the therapeutic orientation of the therapist and the nature of the problems. The child is in a safe environment, and is allowed to choose any items in the playroom and play with them in any way he/she wishes within a minimum number of rules. The therapist acts as a participant-observer. The selection of toys and the way the child plays provide important information about their emotional status and the state of his/her environment.

Below are two photos of one of my playrooms.

Children possess intensive and complex emotions, but they lack the vocabulary to express them. More often than not, they are not allowed or do not feel free to express them. Playing circumvents their defensive mechanisms. A trained play therapist may observe and guide to resolve conflicts, express grief, and empower the child. Sessions of play therapy are also times to learn self-control and boundary.

Children possess intensive and complex emotions, but they lack the vocabulary to express them. More often than not, they are not allowed or do not feel free to express them. Playing circumvents their defensive mechanisms. A trained play therapist may observe and guide to resolve conflicts, express grief, and empower the child. Sessions of play therapy are also times to learn self-control and boundary.

Play Therapy is often used in schools, hospitals and even hospice. There are games that are adapted for individuals with disabilities. Because of the demand for qualified play therapists, many counsellors, social workers and psychologists are taking courses offered by Canadian Association for Child and Play Therapy (CACPT) and American Play Therapy Association (APT).

References

- Axline, V. M. (1947). Play Therapy. New York, NY: Ballantine Books, Inc.

- Brown, S. (2012). The importance of Play for Adults. In M. Tartakovsky (Ed.) Psych Central. http://psychcentral.com/blog/archives/2012/11/15/the-importance-of-play-for-adults/

- Bruner, J. (1983). Play, thought, and language. Peabody Journal of Education, 60(3), 60-69.

- Kalff, D. (1980). Sandplay, a psychotherapeutic approach to the psyche. Santa Monica: Sigo.

- Klein, M. (1955). The Psychoanalytic play technique. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 25, 223-237.

- Landreth, G. L. (2002). Play Therapy: The Art of the Relationship (2nd Ed.). New York, NY: Brunner-Routledge.

- McMahon, L. (2005). The handbook of play therapy. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Peterson, C. (2013). Pursuing the good life: 100 reflections in positive psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.